Maude Royden - 100th Anniversary of the first woman to preach at The Cathdral Church of St. Paul

A century ago, in 1923, Maude Royden came to The Cathedral Church of St. Paul to preach a sermon, the first woman to erver do so at St. Paul’s. And so it is with that historic event that we offered a Lenten preaching series and featured five woman preachers. Scroll down to view the image gallery of the newspaper clippings found in the cathedral’s scrapbook related to Ms. Royden’s vist to the Cathedral.

A Woman's Testimony: 2023 Cathedral Lenten Preaching Series

Jesus's encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well is one of the most beloved and rich stories of the Lenten season. It is also the longest conversation Jesus has in the gospels. During Lent 2023, which marked the 100th anniversary of the first sermon by a woman at the cathedral, we invited five female-identifying preachers to open up the story of Samaritan woman's encounter with Jesus in John 4.

Architecture and Renovations

The first example of Greek Revival architecture in Boston, St. Paul’s was a strong contrast to the colonial “meeting house” appearance of the Park Street Church (1809) across Tremont Street. The light Quincy granite, used for the body of the building, was brought from the quarries on the first railroad operated in the United States. The Ionic columns on the portico are of brown sandstone quarried from the region of Acquia Creek in Stafford County, Virginia.

The first example of Greek Revival architecture in Boston, St. Paul’s was a strong contrast to the colonial “meeting house” appearance of the Park Street Church (1809) across Tremont Street. The light Quincy granite, used for the body of the building, was brought from the quarries on the first railroad operated in the United States. The Ionic columns on the portico are of brown sandstone quarried from the region of Acquia Creek in Stafford County, Virginia.

We have learned recently that the quarry labor which produced this stone was from enslaved persons. This leaves us with the question of “how do we reconcile our past.” You can find the History Committee’s ongoing research on the Cathedral’s ties to the slave economy here.

Stones from St. Paul’s in London, and St. Botolph’s in Boston, England, were included to show unity with the Anglican tradition. As a demonstration of the patriotic fervor that inspired its establishment, a stone from Valley Forge in Pennsylvania was also included. The still unfinished pediment (the triangle at the top of the 6 columns) was intended to contain a carved frieze representing Saint Paul preaching before King Agrippa.

At the turn of the 20th century, sisters Mary Sophia and Harriet Sarah Walker left an estate of more than a million dollars for the purpose of building an Episcopal cathedral (or bishops' church) in the City of Boston. Rather than build a new church, Bishop Lawrence decided the bequest could better be spent on ministry, and he asked St. Paul’s Church to become the Cathedral. On October 7, 1912, St. Paul’s was dedicated as the Cathedral Church for the Diocese. To symbolize that the new Cathedral was indeed “a house of prayer for all people,” Bishop Lawrence arranged for the doors to the pews to be removed.

The interior of the church has undergone repeated and extensive renovation. The current curved apse is a later addition to what was originally a nearly square New England meeting house interior. St. Paul’s also enjoys the distinction of having two beautiful pipe organs, the magnificent Aeolian-Skinner, in the rear (currently in storage waiting for restoration), and the smaller Andover instrument in the chancel.

In 1986, the walls and ceiling painted in a polychromatic style, new granite flooring laid in the aisles, the baptismal font moved to its current location, the majestic but daunting wineglass pulpit replaced by the simpler pulpit-lectern, a free-standing altar constructed, and a dramatic cross bontonnee suspended over the altar.

In April 2014, our Cathedral closed its doors in order to undergo extensive interior renovations; we reopened in Fall 2015.

In 2013, the Nautilus was installed in the Pediment as a symbol of universal invitation and welcome. A piece of public art that sparked some controversy, the Nautilus stands as an inviting symbol of spiritual growth. View a short video about the installation and dedication of this unique work.

In 2014, the historic Church of Saint John the Evangelist, Boston merged with St. Paul’s Cathedral, bringing together the congregations to create a community drawing on the strengths of both. St. John’s historic building was built in 1831 for the Bowdoin Street Congregational Society, led by the Rev. Dr. Lyman Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s father. Notable parishioners included the poet T.S. Eliot, architect Henry Vaugn, and Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. The Chapel of St. John the Evangelist at the cathedral honors the legacy of St. John’s, Bowdoin St. and holds the beautiful Black Madonna that once adorned that church.

In Fall 2015, we reopened our doors after months of extensive interior renovations; our new Cathedral is warm, inviting, and inclusive, a space that embodies our mission of being a house of prayer for all people.

Christmas Covers

One of the resources to which we have access is an assortment of scrapbooks. The scrapbooks include leaflets from Lent, Easter and Christmas services.

Originally published on December 24, 2020.

One of the resources to which we have access is an assortment of scrapbooks. There are a lots of newspaper clippings and other ephemera saved in these scrapbooks, more than we could ever read and properly document for later use. The scrapbooks also have leaflets from Lent, Easter and Christmas services. Some handsomely decorated, and others with a simple border and image.

Click here to view more of these Christmas service leaflets and other photos from the history of St Paul's Church in Boston.

Merry Christmas from all of us on the 200th Anniversary Committee and blessings to you and yours!

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

Mount Hope Cemetery

Our September 3rd article for the 200th history spoke about the deceased who were buried in the crypt of St Paul’s and then moved elsewhere. In the September 17th article we started to answer the question of who was reinterred at Mount Hope Cemetery.

Originally published on October 29, 2020.

Our September 3rd article for the 200th history spoke about the deceased who were buried in the crypt of St Paul’s and then moved elsewhere. In the September 17th article we started to answer the question of who was reinterred at Mount Hope Cemetery. It was a complex question to answer in such a short article. My research started with an Excel Spreadsheet created by a researcher, Marlene Meyers, between 2012 – 2016. I do not know if she ever completed her research, and I do not know how complete the research is. Marlene started to comb through our records to compile a list of those individuals buried in the tombs of St Paul’s, and tried to document where many of them were transferred. Her research revealed many of the names of the deceased who were reinterred in one of the 76 graves that make up the plot at Mount Hope Cemetery. Here is where it gets interesting. Not all graves at Mount Hope are occupied, and, we have more than 76 remains interred in the graves that are occupied.

The earliest reinternments at Mount Hope Cemetery were not full size caskets, but rather, smaller charnel boxes for the bones that were removed from the tombs under St Paul’s. It appears that some or those boxes contain multiple family members/children. Since these boxes did not require a full grave, two burials could occupy one grave. As burial practices changed and cement liners (vaults) were required, those liners started to take up more space than what had been allocated for the 76 graves. In a note dated June 1969 from an unknown source it is recorded that there were six vacancies in Lot 5000 and “Cements Liners are now required, so they probably can only get 4 graves out of graves #72 – 76…” The note goes on to mention “(and #76 is available for 3 more urns of cremated remains.) The last burial in plot 5000 was, April 23, 1988 for Rev. Luis Herrera. An exception was even granted for the placement of a marker for Rev. Herrera, but no such marker exists at the cemetery as of today. Only the solitary Celtic cross installed in 1927 stands as a sentinel to those we love and no longer see. As we approach All Saints Day we offer this prayer from the burial office of the 1789 Book of Common Prayer ALMIGHTY God, with whom do live the spirits of those who depart hence in the Lord, and with whom the souls of the faithful, after they are delivered from the burden of the flesh, are in joy and felicity; We give thee hearty thanks for the good examples of all those thy servants, who, having finished their course in faith, do now rest from their labours. And we beseech thee, that we, with all those who are departed in the true faith of thy holy Name, may have our perfect consummation and bliss, both in body and soul, in thy eternal and everlasting glory; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Necrology linked here.

Excel Spreadsheet with names of former tomb occupants at St Paul’s and re-interments at Mount Hope Cemetery.

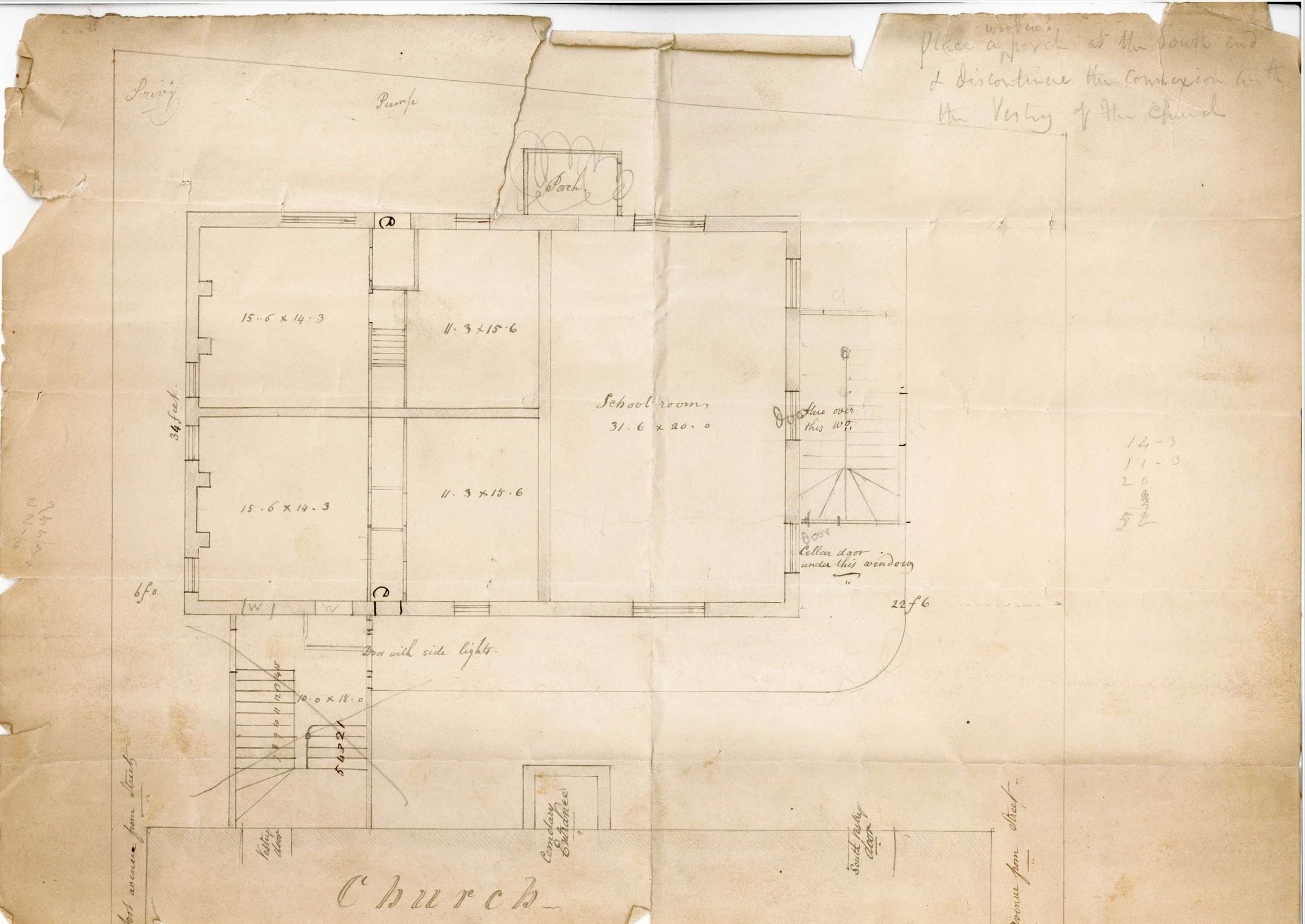

St. Paul's Sunday School Building

In October of 1839 this first school building associated with St. Paul’s Church open for use by the parish. The building was constructed for both a Sunday school, apartments, and other purposes of the parish.

Originally published on October 15, 2020.

In October of 1839 this first school building associated with St. Paul’s Church open for use by the parish. The building was constructed for both a Sunday school, apartments, and other purposes of the parish. The building was built of brick with a slate roof, and copper gutters to conduct water to the cistern. In the contact it is specified that “all the building walls to be lathed & plastered, with stucco cornices in the hall, handsome & of suitable size”. The building was to also provide for two tenement apartments of four rooms with suitable closets. The contract further specified that the wood work to be painted – three coats. The cost of the construction was contracted at $5,400. The contract was signed by James Savage and Henry Codman.

Of note in the scanned images titled St. Paul's Church Boston - Sunday School Building you will see in pencil (top left) the location of the privy in the north-east corner of the property.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

Consecration of the Cathedral Church of St. Paul, Pt. 2

As the city of Boston and the Diocese of Massachusetts continued to grow in the early 20th century, the question was not if a cathedral would be built, but when and how.

Originally published October 7, 2020.

“St. Paul’s Cathedral is yours. I ask you to make full use of it.” -Bishop William Lawrence, October 1912

As the city of Boston and the Diocese of Massachusetts continued to grow in the early 20th century, the question was not if a cathedral would be built, but when and how. Early conversations about building a cathedral in Boston consisted of just that - building a cathedral. One idea was to build a Notre Dame-esque building on an island in the middle of the Charles. Another idea was to build a mini village of structures surrounding and supporting a new cathedral. The problem was that building a cathedral is no small or cheap undertaking. Harriet Sarah and Mary Sophia Walker, two sisters from Waltham, Mass. generously bequeathed the Diocese $1 million (possibly more) to build a bishop’s church in the diocese, and even that was not enough. The Diocese had to get creative, so they turned to St. Paul’s Church.

The congregation at St. Paul’s was dwindling as the city began to spread out, and Bishop William Lawrence saw the location of St. Paul’s as an embodiment of what a cathedral should stand for. St. Paul’s was located in the heart of Boston, steps from the Park Street station. The location of St. Paul’s allowed it to reach thousands of people each day, simply by being there. As Bishop Lawrence saw it in 1912The Cathedral Church of Saint Paul would be a House of Prayer for all people.

Thus, on October 6, 1912, Dr. Edmund Rousmaniere was installed as Dean of the Cathedral in the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts. The following day, a diocesan-wide service was held, and St. Paul’s Church was officially consecrated as the Cathedral Church of St. Paul’s. This consecration was no ordinary service - it was a spectacle. It quite literally stopped traffic as thousands of people gathered for this monumental occasion, full of symbolism. Prior to the service, the clergy robed at Park Street Church. As Frederick Palmer noted, the fact that a Congregational Church would allow Episcopal clergy to use its robing room was “widely recognized as a welcome sign of changed times.” Faculty and students from Episcopal Theological School process through Boston Common and across Tremont street, followed by clergy and the bishops of Rhode Island, Springfield, Maine, and Massachusetts. Traffic was stopped as thousands of onlookers and members of the congregation lined the processional route.

According to Palmer, the “impressiveness” continued after the procession entered St. Paul’s. Dean Rousmainere asked for prayers for the cathedral, for the diocese, and finally for the Church as a whole, evoking several minutes of silence from the entire congregation. In his sermon, Bishop Lawrence spoke proudly about the ideals and institutions of the Cathedral naming it to be a “church which aims to be that of the whole community” and a House of Prayer for all people.

While 108 years have passed, to this day the same words and ideals ring true for the Cathedral church of Saint Paul. The cathedral remains committed to being a House of Prayer for all people, welcoming the lost and lonely, and supporting the fellow parishes of the Diocese of Massachusetts.

Happy 108th birthday, Cathedral Church of St. Paul!

Consecration of the Cathedral Church of St. Paul, Pt. 1

On Wednesday, October 7th , we will celebrate a different anniversary, the 108th anniversary of St Paul's becoming the Cathedral for the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts.

Originally published October 1, 2020.

On Wednesday, October 7th , we will celebrate a different anniversary, the 108th anniversary of St Paul's becoming the Cathedral for the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts. For roughly 92 years St. Paul's was a parish church and as a parish church it would have wide swings in terms of the number of congregants, and also in its finances. On more than one occasion the topic to sell the building and call it quits, or sell and more elsewhere was discuss during a vestry or annual meeting. The proprietors decided each time to stick it out and remain on Tremont St. A series of event would lead to the day, October 7, 1912, when a service was held to dedicate the Cathedral. Next Wednesday we will publish more information about that day in our history and what led to St Paul's becoming the Cathedral.

Check out the full article on the Consecration from October 1912 in The Church Militant !

The Façade of St. Paul

Originally published on September 24, 2020.

Find the full powerpoint here.

Burials and Tombs at St. Paul's, Pt. 2

Our September 3rd article spoke about the deceased who were buried in the crypt of St Paul’s and then moved elsewhere. Additional research has revealed one of the reasons why indoor tombs were abolished in Boston. An article in the Boston Daily Globe, dated January 14, 1879, described the offensive odors of tombs.

Originally published on September 17, 2020.

Our September 3rd article spoke about the deceased who were buried in the crypt of St Paul’s and then moved elsewhere. Additional research has revealed one of the reasons why indoor tombs were abolished in Boston. An article in the Boston Daily Globe, dated January 14, 1879, described the offensive odors of tombs, “ House Judiciary Committee gave hearing to petition of St. Paul’s Church.” described in detail the problem of the smells coming from the tombs. By 1914 that crypt space would soon be converted to what we now know as Sproat Hall. This brought up two questions for Nautilus News readers. Who were the deceased that were reinterred at Mount Hope Cemetery in the Roslindale neighborhood of Boston, and why is there only a single cross as a monument to the deceased?

The second question has a simple answer; a deed restriction! The lot was purchased with the following wording regarding monuments “This lot is sold subject to the condition that no individual headstones or markers are to be erected on the lot.” There are plenty of headstones in the adjoining lots, so it seems strange to not have markers for each individual grave in our lot. The Cathedral purchased Perpetual Care for the lot, so it might have been something as simple as not having to mow around all those headstones. We have no further information regarding this topic.

As for the first question, a May 1914 article in The Church Militant mentioned that 175 bodies remained and that 75 were claimed by the families and reinterred in other locations. The other 100 would be reinterred at Mount Hope Cemetery. The family names of those interred include; Allen, Babb, Brigham, Chapman, Clark, Cordis, Darling, Davis, Eaton, Eddy, Faulkner, Gregory, Hanson, Hayward/Hayword, Henry, Herbel/Herbert(sp), Hodgsden, Holbrook, Hovey/Honey, Hunter, Hunting, Jarvis, Jordan/Jorden, Kinsley, Lawton, Lin/Lind, Marden, McCoy, Merriam, Moussa, Pepper, Perkins, Pike, Prescott, Prowse/Prouse, Randall, Reed, Renouf, Richardson, Rude, Skinner, UNKNOWN, Warner, Washburn, Whipple, Willis, Woods.

We have a very complex Excel Spreadsheet with a lot of information about those burials. We are investigating how to best share this information.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

Burials and Tombs of St Paul’s, Pt. 1

In the earliest years of St. Paul’s the building included tombs and sales commenced in 1822-23. Internal tombs were a common feature in this period; Christ Church (Old North) in Boston’s North End has approximately 1,100 burials sealed in its crypt with active burials between 1732 and 1860.

In the earliest years of St. Paul’s the building included tombs and sales commenced in 1822-23. Internal tombs were a common feature in this period; Christ Church (Old North) in Boston’s North End has approximately 1,100 burials sealed in its crypt with active burials between 1732 and 1860. In 1853 city health officials deemed internal burials to pose a health risk. Tombs were ordered sealed although Old North continued the practice for a few more years. The date of the last internal burial at St. Paul’s requires more research. An article regarding St. Paul’s from The Church Militant (October, 1904) described the then occupied tombs:

“Under the church are to be found numerous tombs which under the early stress of debt it was decided to build. Burial rights were sold for $300 each and were often purchased by people who were in no way connected with the parish. These tombs today have inscribed over their doors the names of some of Boston's best-known families. General Joseph Warren remains rested for 30 years in one of these tombs. In another tomb W H Prescott the historian was buried.”

Over time other occupants would include members of well-known Boston families such as; David Sears, Thomas Wigglesworth, Daniel Parker, Daniel Webster, and Samuel Appleton.

A decade after that article was written the use of the crypt space changed as the need for more space for the living took precedence over the deceased. By 1914 plans were in the works to convert the crypt level of St Paul’s to a parish hall and possibly office space. The Cathedral Chapter purchased a lot at Mount Hope Cemetery in the Roslindale neighborhood of Boston. Of the original 400 buried at St. Paul’s, about 175 were still there at the time of the purchases of the Mount Hope lot – many of the deceased having already been moved by their families in previous years.

We do not know the exact reason for why so many of these burials were moved beforehand. Once could guess it was so that families could have greater control of the remains. Garden cemeteries such as the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass, created in 1831, became all the rage. St Paul families started buying plots at this oasis outside of the city. It would seem a better choice than to have the bones of a family member moved into common grave such as a charnel vault or ossuary, a common practice at the time, in order to make room for new burials.

Those bodies that remained in the tomb at St. Paul’s, roughly 100, were reinterred at Mount Hope Cemetery in a ceremony on May 1, 1914, presided over by Dean Rousimaniere. The plot is marked with only a single large cross to designate the location. There are no individual monuments on the graves.

The lower level of the Cathedral today is now Sproat Hall and there are no longer any burials in (or remaining tombs!) at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

"Firsts" at St. Paul's: William Goodrich's Pipe Organ

The first large organ at the Cathedral was built by the self-taught organ builder William M. Goodrich. Mr. Goodrich is now known by some as ‘the father of the Boston organ-building industry.’

Originally published on August 27, 2020.

The first large organ at the Cathedral was built by the self-taught organ builder William M. Goodrich. Mr. Goodrich is now known by some as ‘the father of the Boston organ-building industry.’ Mr. Goodrich was born in Templeton, Massachusetts in 1777, the son of Ebenezer Goodrich, a farmer in Templeton. William learned to make things while a young man. He repaired and cleaned clocks with another mechanic in town, Mr. Eli Bruce. It was during this time that William helped to construct a small organ with wooden pipes. He learned more about organ construction by making instruments with several other builders.

William Goodrich started constructing church organs himself around 1805 in Boston when he constructed a small instrument for what is now Holy Cross Cathedral. William later built a larger instrument for the Cathedral in 1822.

“The contract for the organ at St. Paul’s Church was signed in 1822, and a smaller organ, loaned to the church by Goodrich, was used while he planned and built the largest organ of his career. It was the first 3- manual & pedal organ to have been built in Boston at that time, and was not completed until the Spring of 1827. It had 26 speaking stops, one of which was a 17-note 16’ Open Diapason in the Pedal. The manual compass was 58 notes, GGG to f3. It was in a classical case 27’ high, 16’ wide and 9 ½’ deep. The building was described as the largest church in Boston at that time, and Goodrich was praised for constructing an organ of sufficient power for it. When the organ builders E. & G. G. Hook replaced the Goodrich organ in 1854, it was sold to Plymouth Congregational Church in Framingham, originally located in the gallery but later moved to a recess behind the pulpit. It remained in use until 1930, when it was replaced by a 3-manual Skinner organ. Skinner refused to salvage any pipework from it, and Goodrich’s magnum opus was presumably destroyed.” (from notes provided by organ historian Barbara Owen)

There is more information to be found in Barbara Owens book The Organ in New England. Much of the information in this short article is found in Ms. Owens’ book as well as an anonymous biographical memoir of William M. Goodrich found at wikisource.org.

- Louise Mundinger

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

Music at the Consecration

In looking at music to include in the 200th service originally planned for May 31st, I wanted to look at American composers from 1820. Who was in Boston at the time? What sort of music was happening in the churches in 1820?

Originally published on August 20, 2020.

In looking at music to include in the 200th service originally planned for May 31st, I wanted to look at American composers from 1820. Who was in Boston at the time? What sort of music was happening in the churches in 1820? I knew that there were singing schools to teach people to read music and sing. The singing schools also used mostly original music called “shape-note” which went along with the music education. Shape-note music was called that because instead of only oval note-heads there were also diamonds, triangles and squares. Each shape corresponded to a musical syllable (e.g. mi-fa-sol-la). People used the syllables first to learn the tunes before using the words. Was shape-note music sung at the Cathedral in 1820? Absolutely not.

I looked at the order of consecration from 1820 and the music included in the service of consecration. After the order for consecration and a complete service of Morning Prayer, the first musical offering was by George F. Handel. After the Litany, Communion and a sermon, the last listed piece was by Handel as well. One of the hymn tunes (Christmas) was by Handel, too. The other listed hymn was Old Hundredth which came over on the Mayflower but started life in Geneva. The Jubilate was sung to a chant by Dr. George K. Jackson who was born in England but lived the last twenty-five years of his life in America. In other words, none of the composers were born in America.

In 1820, as noted in the Vestry minutes, music was important to the congregation because of its role in attracting pew holders to help pay off the debt. The architectural debate between neo-classical and Anglican gothic styles was decided in favor of the former, but as far as music was concerned, Anglican music as heard in England was the order of the day. In fact, the first infant baptized at St. Paul’s Church was the daughter of Matthew S. Parker, an early founder of the Handel and Haydn Society in Boston.

Here’s a list of music heard at the Order of Consecration, June 20, 1820 with orchestra and chorus

“The Great Jehovah is our aweful theme” (from the oratorio Joshua) by G. F. Handel (1685-1756)

Jubilate Deo, a chant by Dr. George K. Jackson (1745-1822)

Hymn: “I’ll wash my hands in innocence,” (sung to the hymn tune Christmas by G. F. Handel.) We still sing the hymn tune Christmas but to the words “Awake my soul, stretch every nerve” #546 in the hymnal. The name of the tune in the hymnal is Siroë after the opera of the same name by Handel.

Hymn: “With one consent let all the earth to God their cheerful voices raise,”sung to (Old Hundredth.) We still sing Old Hundredth for the Doxology, #380 in the hymnal.

Choruses from the Dettingen Te Deum by G. F. Handel o We praise Thee, O God

All the earth doth worship Thee

To Thee all Angels cry aloud

To Thee, cherubim and seraphim

The glorious company of the Apostles praise Thee

- Louise Mundinger

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

Mystery at the Cathedral

The Parish Historians Society has begun the enormous task of creating an inventory of all of the stained-glass windows in the Diocese. The importance of having some record of the wheres and whys of these glass treasures is illustrated by the tale below, told by the Assistant Archivist.

(Katherine Powers, originally published March 7, 1987. Source currently unknown.)

Window, window. Who has the window!

The Parish Historians Society has begun the enormous task of creating an inventory of all of the stained-glass windows in the Diocese. The importance of having some record of the wheres and whys of these glass treasures is illustrated by the tale below, told by the Assistant Archivist.

Many who read this will be surprised to learn that a stained-glass window once found a place in St. Paul's Church— now the Cathedral Church of St. Paul. Sadly enough, the history of this window is not entirely known. Nonetheless, as we attempted in vain to discover the window's provenance and final destination, another—in some ways more interesting—story began to emerge.

We found from the minutes of the annual meeting 1867, that the proprietors of St. Paul's authorized the wardens and vestry to install a stained-glass window "to fill the aperture or space left in the original wall for that purpose” This would, they hoped, dissipate the gloominess of the church's interior.

We realized how wrong we were to have concluded that the window dated from 1867 when we came to the minutes of the annual meeting of 1873 and found the proprietors again authorizing the installation of a stained-glass window in addition to other improvements "in keeping with the place."

This time their plans were accomplished and the results may be seen in the photographs. The window depicts St. Paul preaching to the Athenians. We can find no record, however, of who designed and built the window. The minutes of the proprietors' meetings and of the wardens and vestry are silent on the subject. The newspapers of the day say only that the window "is to be imported from Europe, and will be very beautiful and elaborate."

On either side of the window are the Evangelists. About the renovations, a Boston paper said: "In no church in this city has the interior been so completely changed as in St. Paul's,… The severe simplicity of its old-time appearance is now lost, and for it has been substituted a beauty and richness of adornment which is most attractive. The object which has been aimed at… and which has been happily secured, was to return the classical style in which the architecture… [was] originally conceived." We shall return to the oddness of this statement later.

But what was the meaning of the five year gap between the first authorization of a stained-glass window and its actual installation? And why, indeed, did it have to be authorized twice?

Here we think we have found an answer. From 1859 until 1872 the rector of St. Paul's was the Rev. William R. Nicholson. He was very much a man of Low Church views. Indeed, it seemed that he was positively Calvinistic in his preaching. His sermons were notorious for both length and tedium. In 1860, a large number of St. Paul's parishioners left and established a church in the newly developed and highly prestigious Back Bay. This was Emmanuel Church. Clearly, those who deserted St. Paul's for Emmanuel held evangelical views. This exodus must have greatly altered the make-up of St. Paul's congregation, leaving it with a High Church tendency.

We can imagine what sort of relations existed between the dour Nicholson and his flock after 1860. In fact, we have come across a list of the rectors of St. Paul's Church in the Archives which has "no good!" written beside his name. We can speculate that the proprietors' attempt to install a stained-glass window in 1867 was somehow thwarted by the rector. And, no doubt, relief was mutual when Nicholson left St. Paul's in 1872. (Not long after that he left the Episcopal Church altogether and joined the newly formed Reformed Episcopal Church and became a bishop.)

The congregation of St. Paul's was, we glean, somewhat demoralized by this time. They went almost a year without a rector until they secured the Rev. Treadwell Walden. The proprietors expressed the hope that a new rector and a stained-glass window would attract a more numerous congregation.

All in all, we shall have to say that their hopes were not fulfilled. With more downs than ups, St. Paul's struggled through the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Then Bishop Lawrence stepped in and transformed the church into a cathedral. This saved St. Paul's, but doomed the window. William Lawrence had a particular aversion to stained glass that had been added to buildings that were never meant to be so embellished.

But here, perhaps, we have another puzzle. The proprietors seemed to be quite definite that the addition of the stained-glass window, not to mention the ornamentation of the apse and chancel, was in keeping with the building's original plans. But, as we who spend our time in the archives know, the original interior was, and was meant to be, very simple. The walls of the chancel were inscribed with the Lord's Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the Apostles' Creed. Be this as it may, we do think we must take the proprietors' beliefs in good faith. So, it seems that they somehow translated the idea that St. Paul's is a Georgian building and thus, presumably, follows Grecian ideas of beauty into the notion that, as St. Paul's is a Grecian building, Byzantine decoration complements its design.

But, whatever their reasoning was, its fruit was not to Bishop Lawrence's taste. In 1914, he engaged the services of the architectural firm of Cram and Ferguson to renovate the Cathedral. As it happened, however, the need to raise money for the Church Pension Fund and the World War intervened and work on the Cathedral was postponed. But in 1927, Cram and Ferguson finally executed their commission. The window was removed.

There is reason to think that it was given to another church. But which church is a question we cannot answer. Perhaps it still finds a home in this Diocese. Perhaps one of our readers knows. We hope that in the course of the Parish Historians' inventory we shall come across St. Paul preaching to the Athenians.

-Taken from article written by Katherine Powers, Parish Historian Society, March 7, (1987?)

If you know how she can be reached, please contact Roger Lovejoy at the Cathedral.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

"Firsts" at St. Paul's - Baptism

Sarah Ann Parker was the first infant baptized at the newly consecrated St. Paul’s Church in Boston. Born on June 23, 1820, Sarah Ann was baptized on Sunday, September 10, 1820 by the Rev. Dr. Samuel Farmar Jarvis, Rector of St. Paul’s.

Originally published on July 30, 2020.

St. Paul’s “Firsts”

Sarah Ann Parker was the first infant baptized at the newly consecrated St. Paul’s Church in Boston. Born on June 23, 1820, Sarah Ann was baptized on Sunday, September 10, 1820 by the Rev. Dr. Samuel Farmar Jarvis, Rector of St. Paul’s. Sponsors included her parents Matthew Stanley and Ann Quincy Parker, and Matthew’s first cousin, Sarah Williams Parker, daughter of the second Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, Samuel Parker. Bishop Parker was consecrated Bishop at Trinity Church in New York on September 14, 1804, but was prevented from serving in the role due to his untimely death from gout less than three months later (December 6, 1804). The Bishop’s grand niece Sarah Ann lived in Boston her entire life, marrying Samuel Andrews and raising a family in Roxbury. She died on the 8th of May 1904 in Boston, at the age of 83, and is buried in Hingham.

Asides: Matthew Stanley Parker, the baby Sarah’s father, was a cashier at the newly opened Suffolk Bank in Boston, and one of the founders of the Handel and Haydn Society whose goal was "cultivating and improving a correct taste in the performance of Sacred Music, and also to introduce into more general practice, the works of Handel , Haydn , and other eminent composers."

Also, Sarah Williams Parker, daughter of Bishop Parker, was married to Samuel Hale Parker, Matthew’s brother and thus the bride’s first cousin. In his personal notes regarding parish sacraments, Rev. Jarvis noted both distinctions: “daughter of Bishop P” and “Wife of Samuel Hale Parker.”

The marble font in the picture to the left is from 1851 and is not the one used for Sarah's baptism. It has been a witness to countless baptism here at the Cathedral. The font, now located in Lower Sproat Hall, was designed by Richard Upjohn, whose family moved from England to Boston in 1829. The font was carved by J. Carew.

-Myra Anderson

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

The Neighborhood

When St Paul's opened in 1820, Tremont Street was still a residential neighborhood. The neighborhood soon changes when the Back Bay neighborhood is developed with new luxury townhouses starting in 1859.

Originally published on July 23, 2020.

When St Paul's opened in 1820, Tremont Street was still a residential neighborhood. The neighborhood soon changes when the Back Bay neighborhood is developed with new luxury townhouses starting in 1859. The two photos to the left show remnants of the residential home that were once part of Tremont Street. By the late 1860's Tremont Street will become more of a place of commerce and less residential.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

Telling Our Truth

How do we reconcile our past? Who were our founders and from where did their wealth originate? What should be our relationship to materials we live with and whose origins are in systems of exploitation and extraction at odds with our faith? We have serious community discernment ahead of us, and as the Cathedral begins to investigate our past we also need to look to our future.

Originally published on July 16, 2020.

A few weeks back we mentioned here that St Paul’s church was planned and built for our founders in 1819. The commission went to Alexander Parris and Solomon Willard with a request to construct a church in the style of a Greek Temple to contrast with the existing colonial and gothic structures of the city. The body of St Paul’s church was to be constructed of Quincy granite. The Ionic columns on the portico of what we now call “the porch” were quarried out of sandstone from the Aquia Creek area in Stafford County, Virginia.

Why the different stone and the out-of-state sourcing? While the rest of the building was constructed of local Quincy granite (a very hard, durable stone), perhaps Parris and Willard desired a softer stone more easily manipulated to form the elegant, imposing columns which now support the portico. Crucially, our founders also desired a less expensive stone in order to meet their budget. The search for a softer and less expensive stone began and Parris and Willard eventually selected the quarry in Virginia. That may seem like a long way to go for stone. There must certainly have been a quarry closer to Boston that could supply stone at an affordable price? Why not brownstone from Connecticut. A document from our archive reveals that the “Potomac stone” from the Aquia Creek quarry in Stafford County, Virginia was $12 a ton, and $8 less than stone from Connecticut. Read more about the quarry here and here.

That Aquia Creek quarry had been the source of construction stone for many buildings in the new city of Washington DC, including the Capitol and the White House. We have learned recently that the quarry labor which produced this stone was from enslaved persons. We have learned that the “affordability” of the material purchased in 1819 rests in part on the fact that the people who extracted it from the earth were not paid for their labor.

So our questions are many. How do we reconcile our past? Who were our founders and from where did their wealth originate? What should be our relationship to materials we live with and whose origins are in systems of exploitation and extraction at odds with our faith? We have serious community discernment ahead of us, and as the Cathedral begins to investigate our past we also need to look to our future. Dean Amy recently wrote about what we as the Cathedral are doing to confront and dismantle racism and how we can commit our Cathedral to working towards being an anti-racist institution. Deeper knowledge of our building’s original materials reminds us of past exploitation and of the unfinished work of repentance and reparation.

Selecting the Site of St. Paul's

In this four page document we see the founders’ thought process as they selected a site for St Paul’s in the growing town of Boston.

Originally published July 9, 2020.

In this four page document we see the founders’ thought process as they selected a site for St Paul’s in the growing town of Boston. To give you an idea of what Boston was like in 1819 take a look at the map from 1814. The corridor of what is now Washington St (noted by the orange line on the map.) This road would have led a resident to the extreme end of the town, and it was often referred to as Boston Neck. This narrow “neck” would have then led to the town of Roxbury. In between those two towns was a wetland, now the neighborhoods of the Bay Village, the Back Bay, and The Fenway. These neighborhoods do not yet exist in 1819. The Committee decided to buy a few lots across from the Common that already have buildings and “clear the site of its encumbrances” in order to construct St Paul’s Church. The location of Old North, Trinity Church, and King's Chapel have been marked to give you an idea of how these churches were spaced apart from each other.

Sources from the Cathedral archives.

The Rev. Samuel Jarvis Comes to Boston

The Reverend Doctor Samuel Farmar Jarvis is celebrated as “the first historiographer of the Episcopal Church,” a position to which he was named at the General Convention in 1838. He is best known to us, however, as the first Rector of St. Paul’s Church in Boston. Prior to his installation as pastor of the new church on July 7, 1820, the Rev. Jarvis was already well known to many of the church’s first subscribers. His nature as a prolific recorder of events, along with his keen attention to his reputation and legacy, left us with many clues in the church’s and other institutional archives about the early years of St. Paul’s and his tenure as Rector.

Originally published on July 2, 2020.

The Reverend Doctor Samuel Farmar Jarvis is celebrated as “the first historiographer of the Episcopal Church,” a position to which he was named at the General Convention in 1838. He is best known to us, however, as the first Rector of St. Paul’s Church in Boston. Prior to his installation as pastor of the new church on July 7, 1820, the Rev. Jarvis was already well known to many of the church’s first subscribers. His nature as a prolific recorder of events, along with his keen attention to his reputation and legacy, left us with many clues in the church’s and other institutional archives about the early years of St. Paul’s and his tenure as Rector.

The Rev. Jarvis was born in January 1786 in Middletown, Connecticut, son of that state’s second American Episcopal Bishop Abraham Jarvis. Educated at Yale, Samuel Jarvis was ordained into the priesthood in 1811 at the age of 25. He served at St. Michael’s Church in Bloomingdale, New York, and then as Rector of St. James’ Church in New York City. It was while he was Rector at St. James’ that the Rev. Jarvis came to the attention of some of the influential proprietors of Trinity Church in Boston.

Dudley Atkins Tyng, Reporter of Decisions for the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Boston and enthusiastic member of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, corresponded frequently with the Rev. Jarvis about their shared passions. Tyng and others at Trinity Church, then located at the corner of Summer Street and Bishop’s Way (later Hawley Street) in the South End and one of only two Episcopal (formerly Anglican) churches in Boston, sought over the summer of 1818 to force the Reverend Dr. John Gardiner, Trinity’s Rector, to take on an Associate Rector. They went so far as to fund the new position through the foundation of one of the proprietors and secure a favorable vote of the majority of Trinity’s proprietors, all over the objection of the Rev. Gardiner. Even the Rev. Asa Eaton, Rector of Christ Church in the North End (Old North Church) wrote to the Rev. Jarvis pleading with him to accept the position, while also warning him of the perilous position of the Episcopal Church in New England at that time. The Rev. Jarvis found himself en route to Boston only to be stifled by a message from Gardiner stating he did not support his hiring and dissuading him from continuing.

Tyng, later to become the first Warden of St. Paul’s, and his coconspirators did not give up. The next plan, Tyng explained in a letter to the Rev. Jarvis, was to build a new church “in the nature of a chapel of ease to Trinity Church, the pewholders of which should increase the salary of the assistant minister to a competent support, and in which the rector and assistant should officiate alternately.” Tyng’s hope was to establish the chapel and then make it an independent church once it was filled. There was not enough support among a majority of Trinity proprietors, however, to build a new church. Thereafter, the plan to build a new independent Episcopal Church in Boston, calling the Rev. Jarvis as its Rector, proceeded.

While the new church’s supporters were soliciting subscribers from among disaffected members of other Episcopal churches and the city’s Congregational churches in 1819, the Rev. Jarvis was offered a position as the professor of Biblical Learning at the newly established General Theological Seminary in New York. He informed Tyng of his decision to accept the professorship in order to help the new seminary get started, but with every intention of giving suitable notice of his departure to Boston should the new church be built. When St. Paul’s was built, and the Rev. Jarvis was invited to be its Rector, his departure from the seminary caused a permanent and public rift with the Bishop of New York, John Henry Hobart.

While serving at the seminary, the Rev. Jarvis stayed in constant contact with the subscribers of St. Paul’s and the chairman of the church’s building committee, George Sullivan, offering opinions on its location, construction and subscriptions. Most of Jarvis’ ideas were rejected or ignored, but he was finally received in Boston near the end of June 1820 and installed as Rector shortly afterwards.

In his narrative about his time at St. Paul’s published after his departure in 1826, the Rev. Jarvis lamented, “I was induced to believe that a greater field of usefulness was opened to me in Boston, than in the parishes where I had been for nine years happily settled, or in the Theological Seminary then in its infancy…on my arrival in Boston, I found myself disappointed in almost every particular.”

“Lift up your heads, O ye gates; even lift them up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of glory shall come in.” Psalm 24 (KJV)

Compiled with the assistance of Myra Anderson, Vice Chair of the Cathedral Chapter.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

The Consecration of St. Paul’s Church

The Consecration of St. Paul’s Church in Boston, Friday, June 30, 1820 This coming Tuesday, June 30th, will mark the two-hundred year anniversary of the consecration and opening of St. Paul’s. On the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church we celebrate the Feast of St. Peter & St. Paul on June 29th, that is to say, one of two feast days honoring St. Paul. But how did the founders of St. Paul’s get to that day in June of 1820?

Originally published June 25, 2020.

The Consecration of St. Paul’s Church in Boston, Friday, June 30, 1820 This coming Tuesday, June 30th, will mark the two-hundred year anniversary of the consecration and opening of St. Paul’s. On the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church we celebrate the Feast of St. Peter & St. Paul on June 29th, that is to say, one of two feast days honoring St. Paul. But how did the founders of St. Paul’s get to that day in June of 1820?

Dudley Atkins Tyng

Dudley Atkins Tyng, Esq., was one of the strongest early advocates for the formation of a new Episcopal church in Boston in the early 1800’s. Our archives contain several years of correspondence between Tyng and the Rev. Dr. Samuel Farmar Jarvis. Both men were prolific letter writers, giving many clues about the earliest origins of St. Paul’s Church in Boston. Tyng served as the first warden of the new church and Jarvis was then a young Episcopal priest serving at a church in New York City.

Tyng became a proprietor, the Boston term for member or parishioner, of Trinity Church in Boston, located then at the corner of Summer Street and Bishop’s Way (later Hawley Street) in the South End (what we now call Downtown Crossing).

Tyng and Jarvis began to correspond in the fall of 1818. Jarvis was from Connecticut, son of the second Episcopal bishop of Connecticut Abraham Jarvis. Tyng reported to Jarvis that a group of the proprietors of Trinity were unhappy with Rector John Gardiner’s level of attention to pastoral care and desired to force Dr. Gardiner to accept an assistant. A copy of the offer letter to Jarvis from the trustees of the Greene Foundation (Benjamin Greene and Enoch Hale) offering the position of Trinity Assistant Minister at a somewhat reduced salary than previously discussed is in the archives. The matter got as far as Jarvis being en route to Boston. Jarvis wrote afterwards to Tyng, only to be stifled by a message from Gardiner stating he did not support his hiring and dissuading him from continuing.

A New Church

By late 1818, Tyng and several other prominent men from an array of Boston churches joined forces to form a new Episcopal church, independent of Trinity Church. Tyng continued corresponding with Jarvis to interest him in serving as rector of the new church, keeping Jarvis apprised of their progress. His earliest co-conspirators were Benjamin Greene and Stephen Codman from Trinity Church, and John and George Odin and Subel Bell of Old North. Jarvis was interested in making his mark, particularly in Boston where there was considerable animosity towards the Episcopal Church following two wars fought against the British and a burgeoning Unitarian movement among Congregationalists, the established state church. Jarvis accepted an appointment to the new (General) Theological Seminary in New York in the spring of 1819 while “reserving to myself the right of retiring from the situation, when I may think it expedient, by giving six months’ notice of my intention…if then a new church be built in Boston, I shall be left perfectly open to enter into future negotiations with the vestry.”

By April, 1819, enough men had subscribed to the new church go forward with its incorporation and to begin the search for a location. Tyng relayed the good news to his friend Jarvis, reporting that a committee of nine had been authorized to move forward: Messrs. Odin and Bell from Old North; George Sullivan and Daniel Webster from Brattle Square Unitarian Church (formerly Brattle Street Church, a Congregational Church that had embraced the growing movement toward Unitarianism and was located in the now City Hall Plaza area of Boston); William Appleton, John Armory (Appleton’s father-in-law), Henry Codman (son of Stephen described as “heartsick at Trinity”, became warden of St. Paul’s in 1821 after Tyng returned to his ancestral home in Newburyport due to illness, and William Shimmin from Trinity Church; and Francis Wilby, described only as “of a Baptist congregation.” The committee adopted St. Paul’s as the name of the new church.

The location of the new church was the next step. Jarvis had expressed a preference for the well-established South End, but the new subscribers preferred the West End where there were fewer churches but many residences. Tyng warned Jarvis that not all of the subscribers had committed to purchasing pews, but seemed confident that there were others who would join the church once pews were offered. The group subsequently purchased a lot on Common St (now Tremont St). On March 12, 1820 the formal offer to Jarvis was made from Tyng and George Sullivan on behalf of the proprietors to serve at St. Paul’s. Jarvis accepted the offer on March 17 and the wheels were in motion. More to come on The Rev. Samuel F. Jarvis as we continue this series!

In subsequent letters, Tyng kept Jarvis apprised of the progress of the location and building. The first stone was laid on July 2, 1819. The cornerstone was laid in September, the roof completed at Christmas and then slated. By the first of May the plastering was completed. The pews and pulpit were installed and the finishing touches were in place ahead of the anticipated July completion date. On June 30th, The Rt. Rev. Alexander Viets Griswold, Bishop of the Eastern Diocese, received by the proprietors of the church at the west door, along with The Rev. Samuel Jarvis and other local clergy. They proceeded to the communion table and started the consecration service with the twenty-forth Psalm. It would be another 92 years before St. Paul’s Church would be elevated as the Cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts.

“Lift up your heads, O ye gates; even lift them up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of glory shall come in.” Psalm 24 (KJV)

Compiled with the assistance of Myra Anderson, Vice Chair of the Cathedral Chapter.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

The Founding of St. Paul's

In 1818 a group of individuals, many of whom were not Episcopalians, decided that they wanted to establish a wholly American Episcopal parish. The first Anglican parish in Boston (King’s Chapel) had already been swept up by the Unitarian movement leaving Christ Church (Old North) and Trinity as the remaining two parishes from the pre-Revolutionary days. In 1818 a group of individuals, many of whom were not Episcopalians, decided that they wanted to establish a wholly American Episcopal parish. The first Anglican parish in Boston (King’s Chapel) had already been swept up by the Unitarian movement leaving Christ Church (Old North) and Trinity as the remaining two parishes from the pre-Revolutionary days. The founders purchased a lot on Common Street, now Tremont Street in a neighborhood that was growing.

Originally published on June 18, 2020 with addendum from November 10, 2021.

In 1818 a group of individuals, many of whom were not Episcopalians, decided that they wanted to establish a wholly American Episcopal parish. The first Anglican parish in Boston (King’s Chapel) had already been swept up by the Unitarian movement leaving Christ Church (Old North) and Trinity as the remaining two parishes from the pre-Revolutionary days. The founders purchased a lot on Common Street, now Tremont Street in a neighborhood that was growing.

In 1819 the founders commissioned Alexander Parris and Solomon Willard to construct a Greek Temple to contrast with the existing colonial and “gothick” structures of the city. The body of St Paul’s church would be constructed out of Quincy granite. The Ionic columns on the portico of what we now call “the porch” were quarried out of sandstone from the Acquia Creek area in Stafford County, Virginia (more to come about that story in our report on Reparations and Slavery). The interior is somewhat different from what we now have. Originally, the altar stood in a shallow apse beneath a coved vault supported by free-standing, fluted Ionic Pillars. The pews are now gone, the chancel has been extended, and our generation makes its mark on what is now The Cathedral Church of St Paul. As we investigate our past we will offer a new and more accurate history, different from what has been told in the past. Stay tuned!

Note: the History Committee is conducting ongoing research into the potential involvement of two founding members, William Appleton and David Sears, in the slave economy. You can read more about this history in our report on Reparations and Slavery.

Extracts from: Cathedral Church of St. Paul. (1987). An Anniversary History. Boston, Massachusetts, Edited by Mark J. Duffy.

Images saved on Flickr.com.