Architecture and Renovations

The first example of Greek Revival architecture in Boston, St. Paul’s was a strong contrast to the colonial “meeting house” appearance of the Park Street Church (1809) across Tremont Street. The light Quincy granite, used for the body of the building, was brought from the quarries on the first railroad operated in the United States. The Ionic columns on the portico are of brown sandstone quarried from the region of Acquia Creek in Stafford County, Virginia.

The first example of Greek Revival architecture in Boston, St. Paul’s was a strong contrast to the colonial “meeting house” appearance of the Park Street Church (1809) across Tremont Street. The light Quincy granite, used for the body of the building, was brought from the quarries on the first railroad operated in the United States. The Ionic columns on the portico are of brown sandstone quarried from the region of Acquia Creek in Stafford County, Virginia.

We have learned recently that the quarry labor which produced this stone was from enslaved persons. This leaves us with the question of “how do we reconcile our past.” You can find the History Committee’s ongoing research on the Cathedral’s ties to the slave economy here.

Stones from St. Paul’s in London, and St. Botolph’s in Boston, England, were included to show unity with the Anglican tradition. As a demonstration of the patriotic fervor that inspired its establishment, a stone from Valley Forge in Pennsylvania was also included. The still unfinished pediment (the triangle at the top of the 6 columns) was intended to contain a carved frieze representing Saint Paul preaching before King Agrippa.

At the turn of the 20th century, sisters Mary Sophia and Harriet Sarah Walker left an estate of more than a million dollars for the purpose of building an Episcopal cathedral (or bishops' church) in the City of Boston. Rather than build a new church, Bishop Lawrence decided the bequest could better be spent on ministry, and he asked St. Paul’s Church to become the Cathedral. On October 7, 1912, St. Paul’s was dedicated as the Cathedral Church for the Diocese. To symbolize that the new Cathedral was indeed “a house of prayer for all people,” Bishop Lawrence arranged for the doors to the pews to be removed.

The interior of the church has undergone repeated and extensive renovation. The current curved apse is a later addition to what was originally a nearly square New England meeting house interior. St. Paul’s also enjoys the distinction of having two beautiful pipe organs, the magnificent Aeolian-Skinner, in the rear (currently in storage waiting for restoration), and the smaller Andover instrument in the chancel.

In 1986, the walls and ceiling painted in a polychromatic style, new granite flooring laid in the aisles, the baptismal font moved to its current location, the majestic but daunting wineglass pulpit replaced by the simpler pulpit-lectern, a free-standing altar constructed, and a dramatic cross bontonnee suspended over the altar.

In April 2014, our Cathedral closed its doors in order to undergo extensive interior renovations; we reopened in Fall 2015.

In 2013, the Nautilus was installed in the Pediment as a symbol of universal invitation and welcome. A piece of public art that sparked some controversy, the Nautilus stands as an inviting symbol of spiritual growth. View a short video about the installation and dedication of this unique work.

In 2014, the historic Church of Saint John the Evangelist, Boston merged with St. Paul’s Cathedral, bringing together the congregations to create a community drawing on the strengths of both. St. John’s historic building was built in 1831 for the Bowdoin Street Congregational Society, led by the Rev. Dr. Lyman Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s father. Notable parishioners included the poet T.S. Eliot, architect Henry Vaugn, and Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. The Chapel of St. John the Evangelist at the cathedral honors the legacy of St. John’s, Bowdoin St. and holds the beautiful Black Madonna that once adorned that church.

In Fall 2015, we reopened our doors after months of extensive interior renovations; our new Cathedral is warm, inviting, and inclusive, a space that embodies our mission of being a house of prayer for all people.

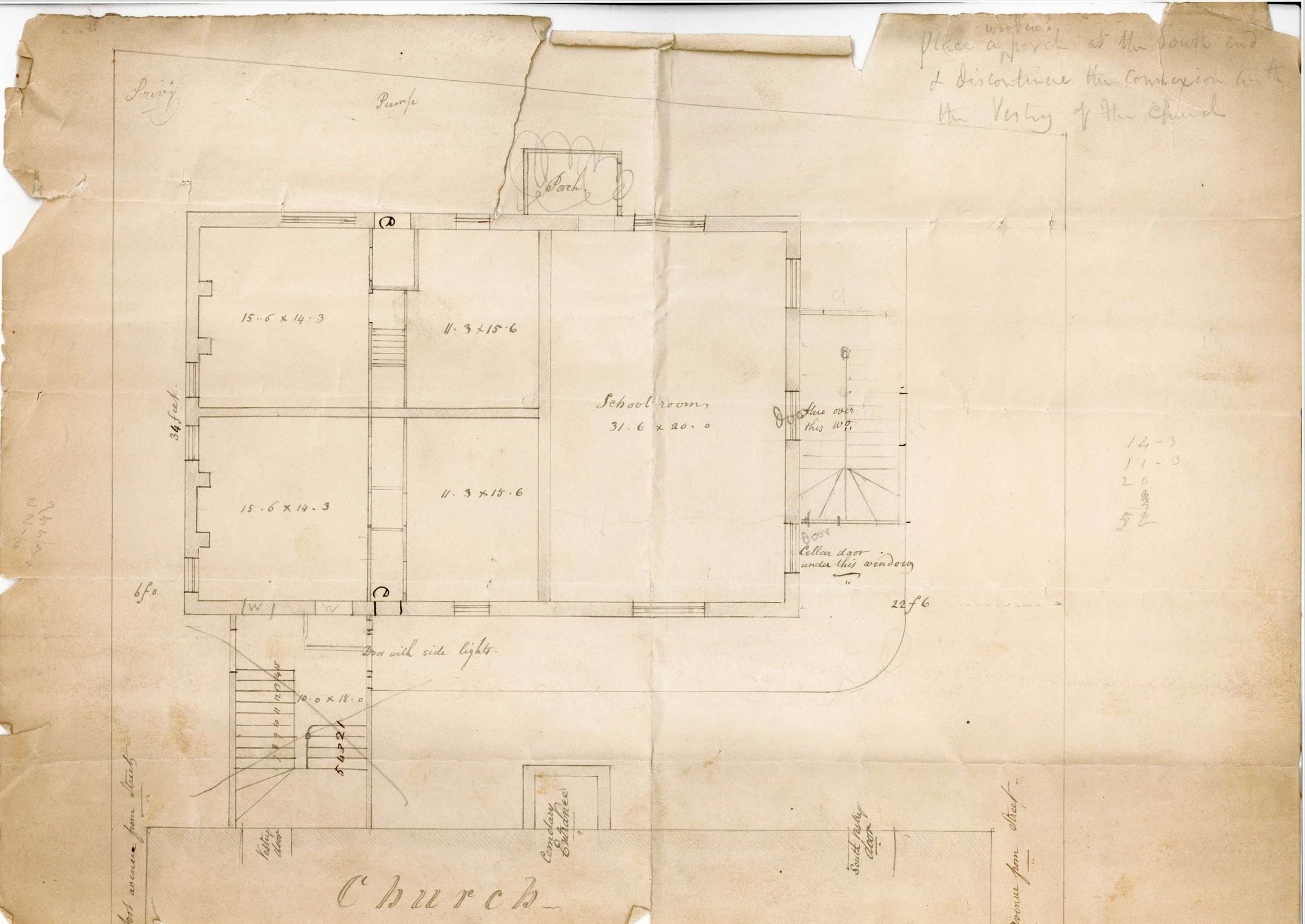

St. Paul's Sunday School Building

In October of 1839 this first school building associated with St. Paul’s Church open for use by the parish. The building was constructed for both a Sunday school, apartments, and other purposes of the parish.

Originally published on October 15, 2020.

In October of 1839 this first school building associated with St. Paul’s Church open for use by the parish. The building was constructed for both a Sunday school, apartments, and other purposes of the parish. The building was built of brick with a slate roof, and copper gutters to conduct water to the cistern. In the contact it is specified that “all the building walls to be lathed & plastered, with stucco cornices in the hall, handsome & of suitable size”. The building was to also provide for two tenement apartments of four rooms with suitable closets. The contract further specified that the wood work to be painted – three coats. The cost of the construction was contracted at $5,400. The contract was signed by James Savage and Henry Codman.

Of note in the scanned images titled St. Paul's Church Boston - Sunday School Building you will see in pencil (top left) the location of the privy in the north-east corner of the property.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

The Façade of St. Paul

Originally published on September 24, 2020.

Find the full powerpoint here.

Mystery at the Cathedral

The Parish Historians Society has begun the enormous task of creating an inventory of all of the stained-glass windows in the Diocese. The importance of having some record of the wheres and whys of these glass treasures is illustrated by the tale below, told by the Assistant Archivist.

(Katherine Powers, originally published March 7, 1987. Source currently unknown.)

Window, window. Who has the window!

The Parish Historians Society has begun the enormous task of creating an inventory of all of the stained-glass windows in the Diocese. The importance of having some record of the wheres and whys of these glass treasures is illustrated by the tale below, told by the Assistant Archivist.

Many who read this will be surprised to learn that a stained-glass window once found a place in St. Paul's Church— now the Cathedral Church of St. Paul. Sadly enough, the history of this window is not entirely known. Nonetheless, as we attempted in vain to discover the window's provenance and final destination, another—in some ways more interesting—story began to emerge.

We found from the minutes of the annual meeting 1867, that the proprietors of St. Paul's authorized the wardens and vestry to install a stained-glass window "to fill the aperture or space left in the original wall for that purpose” This would, they hoped, dissipate the gloominess of the church's interior.

We realized how wrong we were to have concluded that the window dated from 1867 when we came to the minutes of the annual meeting of 1873 and found the proprietors again authorizing the installation of a stained-glass window in addition to other improvements "in keeping with the place."

This time their plans were accomplished and the results may be seen in the photographs. The window depicts St. Paul preaching to the Athenians. We can find no record, however, of who designed and built the window. The minutes of the proprietors' meetings and of the wardens and vestry are silent on the subject. The newspapers of the day say only that the window "is to be imported from Europe, and will be very beautiful and elaborate."

On either side of the window are the Evangelists. About the renovations, a Boston paper said: "In no church in this city has the interior been so completely changed as in St. Paul's,… The severe simplicity of its old-time appearance is now lost, and for it has been substituted a beauty and richness of adornment which is most attractive. The object which has been aimed at… and which has been happily secured, was to return the classical style in which the architecture… [was] originally conceived." We shall return to the oddness of this statement later.

But what was the meaning of the five year gap between the first authorization of a stained-glass window and its actual installation? And why, indeed, did it have to be authorized twice?

Here we think we have found an answer. From 1859 until 1872 the rector of St. Paul's was the Rev. William R. Nicholson. He was very much a man of Low Church views. Indeed, it seemed that he was positively Calvinistic in his preaching. His sermons were notorious for both length and tedium. In 1860, a large number of St. Paul's parishioners left and established a church in the newly developed and highly prestigious Back Bay. This was Emmanuel Church. Clearly, those who deserted St. Paul's for Emmanuel held evangelical views. This exodus must have greatly altered the make-up of St. Paul's congregation, leaving it with a High Church tendency.

We can imagine what sort of relations existed between the dour Nicholson and his flock after 1860. In fact, we have come across a list of the rectors of St. Paul's Church in the Archives which has "no good!" written beside his name. We can speculate that the proprietors' attempt to install a stained-glass window in 1867 was somehow thwarted by the rector. And, no doubt, relief was mutual when Nicholson left St. Paul's in 1872. (Not long after that he left the Episcopal Church altogether and joined the newly formed Reformed Episcopal Church and became a bishop.)

The congregation of St. Paul's was, we glean, somewhat demoralized by this time. They went almost a year without a rector until they secured the Rev. Treadwell Walden. The proprietors expressed the hope that a new rector and a stained-glass window would attract a more numerous congregation.

All in all, we shall have to say that their hopes were not fulfilled. With more downs than ups, St. Paul's struggled through the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Then Bishop Lawrence stepped in and transformed the church into a cathedral. This saved St. Paul's, but doomed the window. William Lawrence had a particular aversion to stained glass that had been added to buildings that were never meant to be so embellished.

But here, perhaps, we have another puzzle. The proprietors seemed to be quite definite that the addition of the stained-glass window, not to mention the ornamentation of the apse and chancel, was in keeping with the building's original plans. But, as we who spend our time in the archives know, the original interior was, and was meant to be, very simple. The walls of the chancel were inscribed with the Lord's Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the Apostles' Creed. Be this as it may, we do think we must take the proprietors' beliefs in good faith. So, it seems that they somehow translated the idea that St. Paul's is a Georgian building and thus, presumably, follows Grecian ideas of beauty into the notion that, as St. Paul's is a Grecian building, Byzantine decoration complements its design.

But, whatever their reasoning was, its fruit was not to Bishop Lawrence's taste. In 1914, he engaged the services of the architectural firm of Cram and Ferguson to renovate the Cathedral. As it happened, however, the need to raise money for the Church Pension Fund and the World War intervened and work on the Cathedral was postponed. But in 1927, Cram and Ferguson finally executed their commission. The window was removed.

There is reason to think that it was given to another church. But which church is a question we cannot answer. Perhaps it still finds a home in this Diocese. Perhaps one of our readers knows. We hope that in the course of the Parish Historians' inventory we shall come across St. Paul preaching to the Athenians.

-Taken from article written by Katherine Powers, Parish Historian Society, March 7, (1987?)

If you know how she can be reached, please contact Roger Lovejoy at the Cathedral.

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

"Firsts" at St. Paul's - Baptism

Sarah Ann Parker was the first infant baptized at the newly consecrated St. Paul’s Church in Boston. Born on June 23, 1820, Sarah Ann was baptized on Sunday, September 10, 1820 by the Rev. Dr. Samuel Farmar Jarvis, Rector of St. Paul’s.

Originally published on July 30, 2020.

St. Paul’s “Firsts”

Sarah Ann Parker was the first infant baptized at the newly consecrated St. Paul’s Church in Boston. Born on June 23, 1820, Sarah Ann was baptized on Sunday, September 10, 1820 by the Rev. Dr. Samuel Farmar Jarvis, Rector of St. Paul’s. Sponsors included her parents Matthew Stanley and Ann Quincy Parker, and Matthew’s first cousin, Sarah Williams Parker, daughter of the second Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, Samuel Parker. Bishop Parker was consecrated Bishop at Trinity Church in New York on September 14, 1804, but was prevented from serving in the role due to his untimely death from gout less than three months later (December 6, 1804). The Bishop’s grand niece Sarah Ann lived in Boston her entire life, marrying Samuel Andrews and raising a family in Roxbury. She died on the 8th of May 1904 in Boston, at the age of 83, and is buried in Hingham.

Asides: Matthew Stanley Parker, the baby Sarah’s father, was a cashier at the newly opened Suffolk Bank in Boston, and one of the founders of the Handel and Haydn Society whose goal was "cultivating and improving a correct taste in the performance of Sacred Music, and also to introduce into more general practice, the works of Handel , Haydn , and other eminent composers."

Also, Sarah Williams Parker, daughter of Bishop Parker, was married to Samuel Hale Parker, Matthew’s brother and thus the bride’s first cousin. In his personal notes regarding parish sacraments, Rev. Jarvis noted both distinctions: “daughter of Bishop P” and “Wife of Samuel Hale Parker.”

The marble font in the picture to the left is from 1851 and is not the one used for Sarah's baptism. It has been a witness to countless baptism here at the Cathedral. The font, now located in Lower Sproat Hall, was designed by Richard Upjohn, whose family moved from England to Boston in 1829. The font was carved by J. Carew.

-Myra Anderson

Photos saved on Flickr.com.

Telling Our Truth

How do we reconcile our past? Who were our founders and from where did their wealth originate? What should be our relationship to materials we live with and whose origins are in systems of exploitation and extraction at odds with our faith? We have serious community discernment ahead of us, and as the Cathedral begins to investigate our past we also need to look to our future.

Originally published on July 16, 2020.

A few weeks back we mentioned here that St Paul’s church was planned and built for our founders in 1819. The commission went to Alexander Parris and Solomon Willard with a request to construct a church in the style of a Greek Temple to contrast with the existing colonial and gothic structures of the city. The body of St Paul’s church was to be constructed of Quincy granite. The Ionic columns on the portico of what we now call “the porch” were quarried out of sandstone from the Aquia Creek area in Stafford County, Virginia.

Why the different stone and the out-of-state sourcing? While the rest of the building was constructed of local Quincy granite (a very hard, durable stone), perhaps Parris and Willard desired a softer stone more easily manipulated to form the elegant, imposing columns which now support the portico. Crucially, our founders also desired a less expensive stone in order to meet their budget. The search for a softer and less expensive stone began and Parris and Willard eventually selected the quarry in Virginia. That may seem like a long way to go for stone. There must certainly have been a quarry closer to Boston that could supply stone at an affordable price? Why not brownstone from Connecticut. A document from our archive reveals that the “Potomac stone” from the Aquia Creek quarry in Stafford County, Virginia was $12 a ton, and $8 less than stone from Connecticut. Read more about the quarry here and here.

That Aquia Creek quarry had been the source of construction stone for many buildings in the new city of Washington DC, including the Capitol and the White House. We have learned recently that the quarry labor which produced this stone was from enslaved persons. We have learned that the “affordability” of the material purchased in 1819 rests in part on the fact that the people who extracted it from the earth were not paid for their labor.

So our questions are many. How do we reconcile our past? Who were our founders and from where did their wealth originate? What should be our relationship to materials we live with and whose origins are in systems of exploitation and extraction at odds with our faith? We have serious community discernment ahead of us, and as the Cathedral begins to investigate our past we also need to look to our future. Dean Amy recently wrote about what we as the Cathedral are doing to confront and dismantle racism and how we can commit our Cathedral to working towards being an anti-racist institution. Deeper knowledge of our building’s original materials reminds us of past exploitation and of the unfinished work of repentance and reparation.

The Founding of St. Paul's

In 1818 a group of individuals, many of whom were not Episcopalians, decided that they wanted to establish a wholly American Episcopal parish. The first Anglican parish in Boston (King’s Chapel) had already been swept up by the Unitarian movement leaving Christ Church (Old North) and Trinity as the remaining two parishes from the pre-Revolutionary days. In 1818 a group of individuals, many of whom were not Episcopalians, decided that they wanted to establish a wholly American Episcopal parish. The first Anglican parish in Boston (King’s Chapel) had already been swept up by the Unitarian movement leaving Christ Church (Old North) and Trinity as the remaining two parishes from the pre-Revolutionary days. The founders purchased a lot on Common Street, now Tremont Street in a neighborhood that was growing.

Originally published on June 18, 2020 with addendum from November 10, 2021.

In 1818 a group of individuals, many of whom were not Episcopalians, decided that they wanted to establish a wholly American Episcopal parish. The first Anglican parish in Boston (King’s Chapel) had already been swept up by the Unitarian movement leaving Christ Church (Old North) and Trinity as the remaining two parishes from the pre-Revolutionary days. The founders purchased a lot on Common Street, now Tremont Street in a neighborhood that was growing.

In 1819 the founders commissioned Alexander Parris and Solomon Willard to construct a Greek Temple to contrast with the existing colonial and “gothick” structures of the city. The body of St Paul’s church would be constructed out of Quincy granite. The Ionic columns on the portico of what we now call “the porch” were quarried out of sandstone from the Acquia Creek area in Stafford County, Virginia (more to come about that story in our report on Reparations and Slavery). The interior is somewhat different from what we now have. Originally, the altar stood in a shallow apse beneath a coved vault supported by free-standing, fluted Ionic Pillars. The pews are now gone, the chancel has been extended, and our generation makes its mark on what is now The Cathedral Church of St Paul. As we investigate our past we will offer a new and more accurate history, different from what has been told in the past. Stay tuned!

Note: the History Committee is conducting ongoing research into the potential involvement of two founding members, William Appleton and David Sears, in the slave economy. You can read more about this history in our report on Reparations and Slavery.

Extracts from: Cathedral Church of St. Paul. (1987). An Anniversary History. Boston, Massachusetts, Edited by Mark J. Duffy.

Images saved on Flickr.com.